Each generation of The Proprietors of Green Mount has maintained and enhanced the natural and manmade attributes which combine to make this so unique a burial place. By them, the sacred trust has been kept, and will be kept for all time to come.

It is our hope that your appreciation for Art, History, and Nature is reawakened as you visit Green Mount Cemetery.

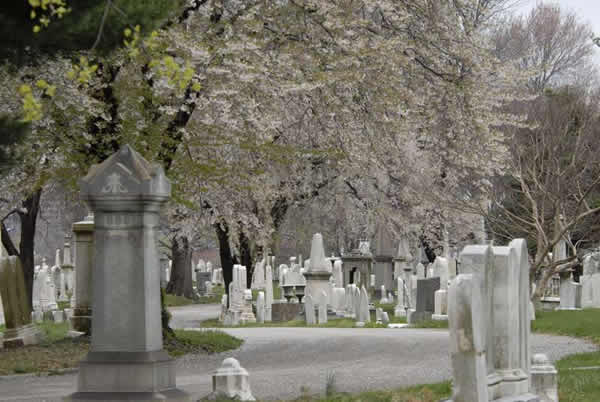

Nature and Landscape at Green Mount

Since its beginning in 1838, Green Mount has been described as a rural or garden cemetery. The idea behind this type of cemetery began in Paris at the turn of the nineteenth century when Napoleon established the famous Père Lachaise Cemetery in 1804. Burials had been banned inside the city because of health concerns and lack of available space, which explains Père Lachaise’s location well outside the city’s then existing boundaries. The site was chosen for its rising ground and mature trees, and it became even more dramatic with new cobbled streets and grand monuments. Père Lachaise is the burial site for thousands of notables, and today it is in every tourist guide to the city.

In the United States, the first rural garden cemetery was Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts, just four miles west of Boston. In 1831 Dr. Jacob Bigelow gathered together a group of prominent citizens who joined with the newly formed Massachusetts Horticultural Society to found the new cemetery on seventy-two acres of land selected for its hills, ponds, streams, and mature hardwood trees.

As in Paris, lack of urban burial space and public health concerns were two reasons for founding a new cemetery, but Mount Auburn’s success was insured by more abstract reasons. Mid 19th century America wanted more than a pastoral resting place for its dead; it wanted a respite from the stresses and trials of urban life for the living.

The twin factors of immigration and industrialization changed the physical and social climate of 19th century American cities. An increased labor supply from immigrants and from workers leaving farms to work in the city fed the engine of industrial growth. In 1800, seventy-five percent of the population engaged in agriculture. By 1850, it had decreased to fifty percent and went unabated. Rapid industrial growth meant wealth for a few, middle class status for some, and poverty for many. It also meant overcrowded cities with no public parks and a newly urban population nostalgic for the perceived “simplicities” of nature.

Romanticizing nature was both a response to the times and a convenient solace for city dwellers feeling the pressures of urbanization. The Romantic Era began in mid 18th century Europe as a reaction to the intellectualism of the Enlightenment Movement and to the rapid changes produced by the Industrial Revolution. Romanticism emphasized emotion rather than intellect, mystery rather than clarity, and individualism rather than the rigid norms of society. Aesthetically expressed in literature, art, music, and politics, Romanticism was the perfect vehicle to soothe one’s angst about radical change and disruption.

When the new rural garden cemeteries were planned, they were not laid out on a grid like city streets nor were they treeless like newly built neighborhoods. Instead, they were designed in the “picturesque” style found on English country estates: winding paths and streets; vistas and varied scenic overlooks; water features of every description; and a landscape enhanced by the planting of thousands of trees and ornamental shrubs. In short, it was an idyllic landscape. No wonder that thousands of city dwellers spent Sunday afternoons picnicking and strolling in their new “park”.

It is also no wonder that these rural garden cemeteries were the early prototypes for the large city parks built in the second half of the 19th century, the first of which was Central Park in New York in 1858. Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, the designers of Central Park, would surely have visited Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery and have been influenced by it.

Baltimore too gained its own rural garden cemetery after Samuel Walker visited Mount Auburn in Massachusetts and came home to muster support for purchasing sixty eight acres of land to establish Green Mount in 1838.

Green Mount as a Rural Garden Cemetery

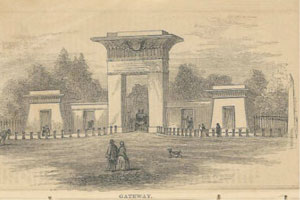

The plan for Green Mount was laid out by Benjamin Henry Latrobe, II; son of B. H. Latrobe, one of several architects for the nation’s Capitol. Latrobe the son was both a lawyer and a civil engineer, his most acclaimed achievement being the Thomas Viaduct built for the B & O Railroad and completed in 1834. The Viaduct is the largest stone arched bridge with an arc in the world and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It is still in use today for commuter trains.

Latrobe’s design for Green Mount incorporated the features typical in rural garden cemeteries of the day: winding paths, mature trees, grassy knolls, shaded dells, and of course, many impressive monuments and statues.

The highest elevation is approximately 190 feet above sea level and affords a panoramic view of Baltimore city, especially in winter when the trees have lost their leaves. “Oliver’s Walk” is one path which follows the natural terrain around the crest of the Cemetery. It is possible that Robert Oliver, the original owner of the property, may have established the path himself when he lived at his country estate. On this walk the stroller passes the Mausoleum and comes near the grave of Olivia Cushing Whitridge, the first interment of the Cemetery.

There are two underground streams flowing through Green Mount, both of which were channelized in the 19th century. A small spring house was constructed in 1897 in the southeast portion of the Yew Area and still holds a clear pool of water in a moss draped basin.

Green Mount is shaded in summer by towering hardwood trees of oak, maple, walnut, linden, sycamore, gingko, ash, locust, chestnut, beech, and one katsura. Smaller species include: holly, cedar, dogwood, sassafras, cryptomeria, crepe myrtle. There is even one giant boxwood standardized as a tree. These mature hardwood trees also provide autumn color, especially when the ginkgos turn their characteristic brilliant yellow.

Bird watchers are visitors to Green Mount Cemetery and have reported sightings of species not often associated with city dwelling: hawks, falcons, woodcocks, owls, and on one rare occasion, a wild turkey. Of course there are the usual woodpeckers, cardinals, ravens and other bird species common to urban life. Fox sightings have been reported as well.

This urban oasis of green still serves the purposes for which the rural garden cemetery movement of the 18th century was intended, as a place of nature and a respite of calm in the city.

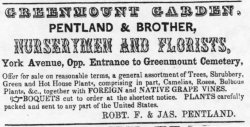

James Pentland: Green Mount’s First Gardener:

Like most of 19th century Baltimore’s population, James Pentland was an immigrant. At age eleven or possibly twelve, he came from Ireland with his family to the port of Philadelphia. There he apprenticed in the floriculture trade and moved to Baltimore around 1843. Pentland’s first job in his newly adopted city was as the gardener of Green Mount Cemetery.

Apparently James Pentland flourished. In 1849 he purchased land directly across from the main gates of the Cemetery on Greenmount Avenue and opened his own nursery business. He grew bedding plants, exotic grapes, roses, and cut flowers. The federal census of 1850 lists James Pentland as a twenty-nine year old florist residing at 1510 Greenmount Avenue with his wife Rose, two sons, and several other household members who may or may not have been related.

The Pentland nursery business prospered over the years. An article in the Baltimore Daily Gazette, dated September 26, 1864, described the grapes from his “well-known nursery” as “magnificent specimens” of the “Black Hamburg, Muscat of Alexandria and several other choice varieties”. Another article some years later spoke of Pentland’s business as “one of the oldest and largest in Baltimore in this line of industry” and of Pentland himself as an “accomplished proprietor with marked ability and signal success”.

Not surprisingly, James Pentland also became prominent in the affairs of the city. In addition to being president of the local floral trade association, he was on the Board of managers of the Maryland Institute of Art and was elected to the Maryland House of Delegates as a Representative for Baltimore City in 1868.

James Pentland died in 1902 at the age of eighty-one and is buried, appropriately, in the family plot in Green Mount Cemetery.

One of Pentland’s legacies is a rose which he hybridized while serving as head gardener. In the words of Stephen Scanniello, a long time rose expert and former curator of the Cranford Rose Garden at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden:

“The name, “Green Mount Red” is a study name, meaning that we don’t know the true, or original, name of this rare rose. Only two plants of this small–flowered red rose are known to exist today. The oldest grows in Baltimore’s Green Mount Cemetery; the other is newly planted on the grave of Mr. George F. Harison in Trinity Church Cemetery. Harison’s plant was grown from cuttings taken from Green Mount. It’s possible that this rose may be the long-lost 1854 variety ‘Beauty of Greenmount’ [sic], a red shrub rose created by James Pentland while he was the head gardener of Green Mount Cemetery. Pentland’s rose was included in the inventory of 19th century New York nurseries.”

Contributing Authors

Judith Smith, member of Friends of Maryland’s Olmsted Parks and Landscapes. http://www.olmstedmaryland.org/

For more on James Pentland visit: http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~ruppert/Pentland/

Stephen Scanniello, President of the Heritage Rose Foundation, member of the American Rose Society, author of A Year of Roses, and co-author of A Rose by Any Name.

http://www.heritagerosefoundation.org/

http://www.ars.org/